Hand Dominance Development in Children

Affiliate and Referral links are used below to promote products I love and recommend. I receive a commission on any purchases made through these links. Please see my disclosure policy for more details. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

I often see questions surrounding the topic of hand dominance. How does it develop and when should we expect children to choose which hand they will write or use scissors with? When should we be concerned about children switching hands between or in the middle of tasks? Today I am going to look over some research and help answer some of these questions along with hand dominance development in children.

You will see hand dominance referred to as using a “preferred hand” or “dominant hand” for activities. In short, does the child prefer their right hand or left hand to complete tasks?

When children enter preschool is when a lot of us start wondering if they will be right or left-handed. Handedness is a very complex task and its development actually starts in the womb.

What is Hand Dominance?

Hand dominance, or handedness, is controlled by the brain and is contralateral, meaning the right hemisphere/side of the brain controls the left hand, and the left hemisphere/side of the brain controls the right side.

It is also known that 90% of the world's population is right handed. This has been tracked for thousands of years and is a trend that has continued for up to 5,000 years (Coren and Porac, 1977)

In the nineteenth century, Paul Broca, a neurologist, suggested that language control and hand preference were connected.

For most, language is centered in the left hemisphere of the brain (87-96% of the population), however, not everyone is right-handed, obviously. For a small percentage of the population, language and bilateral use are controlled by the right hemisphere of the brain. (Source: Sperry, 1974; Khedr et al., 2002; Vogel et al., 2003; Forrester et al., 2013, Annett, 1981a,b; Khedr et al., 2002).

You would think this would account for those who are left-handed, but even in left-handedness, 60-73% of those with a dominant left hand, language is still centered in the left hemisphere of the brain.

All of this leads to a lot of debate on whether or not language function and handedness are connected.

There are certain things that researchers look at when assessing hand dominance and that is DIRECTION, DEGREE, PREFERENCE, AND PERFORMANCE.

Direction refers to whether or not a person is left or right handed.

Degree refers to how strongly a person prefers one hand over the other.

Preference identifies the preferred hand for completing tasks.

Performance looks at the abilities of the left and right hand to perform various tasks.

Performance can greatly affect preference, since a child or person will choose a preferred hand to complete a task based on how that hand performs the task (or the ability of that hand).

Developing handedness or preference for one hand to complete a tasks allows the brain to make these movement automatic. If one side of the brain is responsible for certain types of movement and tasks, it is easier for these tasks to be refined and automatic, which can affect their performance and ability to complete tasks.

The more a child uses one hand for specific movements, the more opportunity their brain has to refine these movements and make them automatic. This frees up the brain to think about other cognitive tasks instead of the motor movement component of activities.

Functionally, this can affect how a child holds scissors and cuts or how they hold a pencil and their handwriting legibility.

Typical Hand Dominance Development in Children

Hand preference is something that develops as a baby is starting to reach and explore the world around them. This starts in the womb as a baby starts to reach their hand to their mouth and suck their thumb.

Hand preference development begins when a baby start to grasp objects with their hand. This starts as an automatic reflex and then moves to grasping patterns that we see with babies and young toddlers.

The grasp reflex begins in the womb and continues until a baby is about 6 months old. You can see this reflex very easily when you place your finger inside a baby's hand: they will automatically wrap their fingers around yours. This is an automatic response and you will see it start to disappear to be more functional around 6 months old.

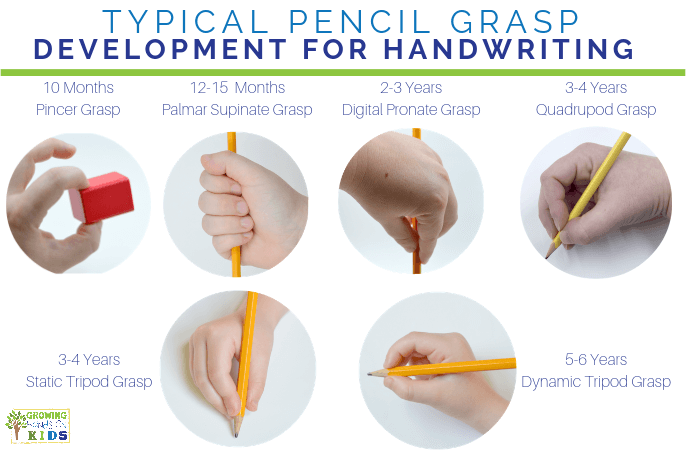

After the grasping reflex has disappeared, children will move through some typical grasping patterns that I wrote about here.

You may start to notice your child using a preferred hand for grasping or completing different everyday-life skills or fine motor activities by age 2. It is important to remember though that they will switch sides often and this is very typical.

Some research suggests that the preferred hand a child uses at age 18-30 months is the hand they end up using consistently later on (Archer, Campbell, Segalowitz 1988). This could account for up to 60-70% of children.

That still leaves with at least 30-40% of children who may have not decided on a preferred hand until later.

There is a lot of debate on what age we should expect children to pick a preferred hand and use adult-like hand patterns.

Some researchers (Archer et al., 1988; Longoni and Orsini, 1988; McManus et al., 1988) have suggested that the direction (whether they are left or right-handed) hand preference is fixed at age 3. They went on to explain that the degree (how strongly they prefer that hand) increases between the ages of 3–7 and more gradually until the age of 9.

If this is the case, a child's hand preference cannot be reliably assessed until 4 years of age (McManus, 2002). Other researchers have noted that children 3–4 years of age do not reliably select the preferred hand and that it is not until the age of 6 that a clear preference can be observed (Bryden et al., 2000a).

When researchers have assessed handedness with a variety of tasks such as pegboards and finger tapping, they found that children between the ages 3-6 showed more variety in choosing a hand and also had slower movements. Children over the age of 6 increased their speed with adult-like movements showing between the age of 10-12.

This suggests that experience and the ability to refine and practice movements is crucial as children develop hand preferences.

Other Factors That Affect Handedness

There are a few factors that can affect handedness and that includes sensori-motor experiences, environmental factors, and genetics.

Genetics may play a role since it is more likely that a child who has two parents who are right-handed will to be right-handed themselves. Those who gravitate towards the left, typically have at least one parent who is left-handed.

Again, this does not account for personal development of handedness. Despite a genetic disposition to using one hand vs the other, a child still develops a hand preference based on more than factors than genetics.

Other factors can include sensori-motor behavior that is observed in the womb, such as thumb sucking, and continues after a baby is born with positioning and grasp reflex strength. As they build on these basic motor skills, refinement of those skills continues as they grow and age.

Environmental factors can influence handedness such as what type of tool or object a child is reaching for. Is it easier for them to grasp it with the left or right hand? Is the toy placed on their right or left side? This may influence which hand they use to reach for and grasp an object.

Children Who Struggle With Hand Dominance

The topic of handedness is really fascinating and there is so much to comb through and learn about when it comes to how handedness develops.

But let's get down to the nitty-gritty, what does this mean for our children who are struggling? How can we know when to help a child who may be struggling with hand skills?

It all comes down to function and ability. A child is likely to pick the hand that has the ability to complete a task. Things that can affect this include the strength of the hand, their ability to cross midline, bilateral coordination of the hands (using both hands together to complete a task), and the ability to automate the movements needed for tasks such as handwriting, using scissors, buttoning etc.

If a child continues to switch between hands for the same type of activity, it makes automatic movement or learned movement for specific activities harder to achieve. The brain is still having to use both hemispheres to complete a task, instead of focusing on refining these movements and freeing up the brain for other cognitive tasks.

By the time a child enters Kindergarten (or age 5-6), we should start to really see a preferred hand for these types of tasks. Remember that these movements are still being refined to adult like movements until age 10-12. But, we still should start to see a consistent use of one hand vs. the other.

If a child has reached the end of Kindergarten and is still switching between hands often for tasks such as scissors or handwriting, this could be a red-flag that we want to address.

We will want to go back and look at the basic motor function of the hand. How are they able to grasp and hold objects? Is there a lack of strength or bilateral coordination that we need to address? Are there environment factors of positioning, or lack of experience and exposer to activities that need to be addressed?

Does the child struggle with crossing the midline and is this impacting the function of lateralization in the brain hemisphere that needs to happen in order for movements to be automatic? Do we need to address the tools being used to help promote success with these tasks?

In the next post we will look at activities and strategies that can help children who are struggling with hand dominance.

For more resources like this one, check out the links below:

- Foundational Skills Needed for Handwriting Mechanics

- 5 Tips for Difficulty with Scissor Skills for Kids

- Which Fine Motor Skills are Important for Handwriting

References:

Archer, L.A., Campbell, D., and Segalowitz, S.J. (1988) A prospective study of hand preference and language development in 18‐ to 30‐month olds: I. hand preference, Developmental Neuropsychology, 4:2, 85-92, DOI: 10.1080/87565648809540395

Bryden, P. J., Pryde, K. M., and Roy, E. A. (2000a). A performance measure of the degree of hand preference. Brain Cogn. 44, 402–414. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1999.1201

Bryden, P. J., Pryde, K. M., and Roy, E. A. (2000b). A developmental analysis of the relationship between hand preference and performance: II. A performance-based method of measuring hand preference in children. Brain Cogn. 43, 60–64.

Coren, S., and Porac, C. (1977). Fifty centuries of right-handedness: the historical record. Science 631–632. doi: 10.1126/science.335510

Forrester, G. S., Quaresmini, C., Leavens, D. A., Mareschal, D., and Thomas, M. S. (2013). Human handedness: an inherited evolutionary trait. Behav. Brain Res. 237, 200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.037

Khedr, E. M., Hamed, E., Said, A., and Basahi, J. (2002). Handedness and language cerebral lateralization. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 87, 469–473. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0652-y

Longoni, A. M., and Orsini, L. (1988). Lateral preferences in preschool children: a research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 29, 533–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00744.x

McManus, I. C., Sik, G., Cole, D. R., Mellon, A. F., Wong, J., and Kloss, J. (1988). The development of handedness in children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 6, 257–273. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1988.tb01099.x

McManus, C. (2002). Right Hand, Left Hand: The Origins of Asymmetry in Brains, Bodies, Atoms, and Cultures. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Scharoun SM and Bryden PJ (2014) Hand preference, performance abilities, and hand selection in children. Front. Psychol. 5:82. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00082

Sperry, R. W. (1974). “Lateral specialization in the surgically separated hemispheres,” in Neurosciences Third Study Program Vol. 3, eds F. Schmitt and F. Worden (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 5–19.

Vogel, J. J., Bowers, C. A., and Vogel, D. S. (2003). Cerebral lateralization of spatial abilities: A meta-analysis. Brain Cogn. 52, 197–204. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00056-3

Heather Greutman, COTA

Heather Greutman is a Certified Occupational Therapy Assistant with experience in school-based OT services for preschool through high school. She uses her background to share child development tips, tools, and strategies for parents, educators, and therapists. She is the author of many ebooks including The Basics of Fine Motor Skills, and Basics of Pre-Writing Skills, and co-author of Sensory Processing Explained: A Handbook for Parents and Educators.

Great article. Is it possible to get a print friendly version?

Thank you for this article. If a child was forced to switch from to left, is there anyway to make the child go back to her preferred hand?